- Home

- Mary Burns

The Reason for Time

The Reason for Time Read online

Table of Contents

Also by Mary Burns

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Epigraph

Sandburg poem

Author's Note

Monday, July 21, 1919

Tuesday, July 22, 1919

Wednesday, July 23, 1919

Thursday, July 24, 1919

Friday, July 25, 1919

Saturday, July 26, 1919

Sunday, July 27, 1919

Monday, July 28, 1919

Tuesday, July 29, 1919

Wednesday, July 30, 1919

Epilogue

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About The Author

Also Published By Allium Press Of Chicago

Also by Mary Burns

Suburbs of the Arctic Circle

Shinny’s Girls and Other Stories

Centre/Center

The Private Eye: Observing Snow Geese

Flashing Yellow

You Again

THE REASON

FOR TIME

Mary Burns

ALLIUM PRESS OF CHICAGO

Allium Press of Chicago

Forest Park, IL

www.alliumpress.com

This is a work of fiction. Descriptions and portrayals of real people, events, organizations, or establishments are intended to provide background for the story and are used fictitiously. Other characters and situations are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not intended to be real.

© 2016 by Mary Burns

All rights reserved

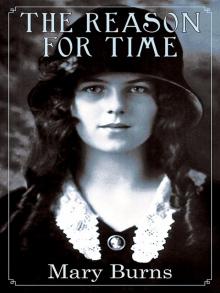

Book/cover design by E. C. Victorson

Front cover image:

Portrait of a young woman

photographer: Mathew J. Steffens

from the collection of Thomas Yanul (1940–2014)

Author photo by Rachael King Johnson

Print ISBN: 978-0-9967558-1-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-9967558-2-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Burns, Mary, 1944 author.

Title: The reason for time / Mary Burns.

Description: Forest Park, IL : Allium Press of Chicago, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002001 (print) | LCCN 2016008555 (ebook) | ISBN

9780996755818 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780996755825 (pub)

Subjects: LCSH: Irish Americans--Chicago--Fiction. | Chicago

(Ill.)--History--20th century--Fiction. | Nineteen tens--Fiction. | United

States--History--1919-1933--Fiction. | GSAFD: Historical fiction.

Classification: LCC PR9199.3.B7923 R43 2016 (print) | LCC PR9199.3.B7923

(ebook) | DDC 813/.54--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002001

For the previous Marys

A secret is a grave/But who sees me?

I am my own hiding place.

Gaston Bachelard/Joë Bousquet

WORKING GIRLS

The working girls in the morning are going to work—

long lines of them afoot amid the downtown stores

and factories, thousands with little brick-shaped

lunches wrapped in newspapers under their arms.

Each morning as I move through this river of young-

woman life I feel a wonder about where it is all

going, so many with a peach bloom of young years

on them and laughter of red lips and memories in

their eyes of dances the night before and plays and

walks.

Green and gray streams run side by side in a river and

so here are always the others, those who have been

over the way, the women who know each one the

end of life’s gamble for her, the meaning and the

clew, the how and the why of the dances and the

arms that passed around their waists and the fingers

that played in their hair.

Faces go by written over: “I know it all, I know where

the bloom and the laughter go and I have memories,”

and the feet of these move slower and they

have wisdom where the others have beauty.

So the green and the gray move in the early morning

on the downtown streets.

—Carl Sandburg, Chicago Poems

Author's Note

The Reason for Time is told in the voice of a young woman who lived through ten tumultuous days in Chicago, in July 1919. Words she uses reflect the language of her time, and what we now consider to be ethnic slurs are in no way intended to be disrespectful.

Monday, July 21, 1919

The dirigible fell that fast gusts of pushed out air rustled my skirt around my ankles, and wasn’t I across Jackson Boulevard by then, not knowing whether to tilt back my head to look or duck for cover? First the spreading shadow, then the odd shout sprung up from here and there, bunching into a roar when that big silver egg dropped flaming from the sky right onto the Illinois Trust and Savings Bank. And one of the parachutes meant for escape? Didn’t that fall flaming too, a candle soon snuffed on the ground barely a block beyond. Others floated through the billows so thick you couldn’t see what was attached to them, but you hoped it was someone made it out alive. “Look!” But where to aim your eyes first? The Wingfoot Express. Looked so impressive on the ground, it had, over there at the Grant Park field, but knowing how flimsy it turned out to be had me wondering what fools’d wanted to go along for what the papers called a joy ride. No joy for them that day, maybe never again.

The screaming started with the plunging made it more terrifying. A great boiling soup of sound, roar of fire, shattering glass, clanging bells, keening voices, clattering metal. Then an unholy minute, sure not even as long as a minute after the explosion, when them gas tanks fueled the airship went up and I might a been deaf. It was that still I thought I’d been killed, like all them in the bank and the fellows crashed into it. But I was not about to die then, no, not killed, only bleeding, and just a dab of blood it was on my neck, like something’d bit me. Window glass spitting way across Jackson Boulevard, could a been, and no one caring or even remarking that slight injury or me at all in the crush, as half the bodies in the Loop shoved forward, despite the police hollering at us all to make way for the big-wheeled fire trucks rolling in. The brave ones spilled off the trucks and aimed their ladders up the side of that stricken building, poked their fat hoses into the busted out windows to douse the inferno inside. Above the usual stink of smoke and horse droppings, the throat-catching billows of oily gas and also a singeing, like hair being marcelled in a hot iron.

We could only imagine the terrors. And who were all them yelling in there? The girl with the stained fingers took the envelope my boss Mr. R gave me to deliver, being too proud to go begging himself? Me admiring the lace collar on her shirtwaist, nice and narrow like a delicate frame around the throat of her maybe one of them hollering for help?

First the shock, then the curiosity and the crowd livened with the sort of thrill comes with fright, same as when the Mauretania steamed into New York harbor, everyone rushing the decks, and me and my sister Margaret—just girls—getting near lost in the excitement as I might well have become lost on Jackson Boulevard the Monday that July. I am small, I have always been small, and I early learned to make my way how best I could. Still, being closer to the ground than most, I never saw much of the goin’s-on at the Illinois Trust and Savings. The man directly in front of me in his summer jacket, sweat bubbling above his starc

hed collar, and all them in straw boaters or fedoras conspired to block my view. A pair of overalled colored boys too, maybe sixteen and just stepped off the northbound train, could a been, exclaiming in their funny voices, “Lawdy me,” just like in the minstrel acts. Then laughing as if they found each other comical. From somewhere in the throng a newsie hollered,

AIRSHIP CRASHES! BIG SLAUGHTER!

His voice too tweaked by wherever his family’d dragged him from. Bold as brass they tended to be, the newsies. No papers could be printed instant as that.

Just minutes before, I’d waited for that lace-collared correspondent’d come through the wire cage from the grand rotunda with all its marble, and the light shining down through the glass above, throwing patterns over rows of desks with their identical lamps lit, though it was full afternoon. Lamps burning under shades the shape of flowers, prettier than we had at our place. The wire cage around the girls working on their letters and adding the day’s receipts. How’d they got out? Or had they? God have mercy on their souls.

What a time, too, it being near five o’clock and people streaming out the office buildings. More and more people crowding into the street, all of them after joining we many already there and seeking what protection we could beneath the shoulders of the big bank buildings. Fair to perishing as the heat of the day pooled into that hour, yet jostling together all the same, claimed by the event, opinions motley as the crowd. How could I leave? The rest thinking the same, no doubt, for we milled around and rumors spread faster than the influenza took Packy the year before. Hundreds dead inside, including the bank president, who was to receive Éamon de Valera that day and wasn’t he from our home place, Margaret’s and mine, of Ennis, de Valera? And didn’t he want money to take back for the new republic? Then came the report that it was not de Valera at all but Mr. Armour himself who’d been inside with the bank president.

“Counting his money!”

“Fried like his bacon!”

“God rest his soul, poor man.”

“What soul? No heart. No soul!”

The crowd talking to itself, searching for reasons. Flying too low over the Loop, the Wingfoot’d been, and this to please the photographer who paid the dearest price for his ambition was one theory you could get for free. Another blamed the crew for smoking cigarettes inside the blimp. Like a regular conversation and all, except flattened beneath the haze of the sun and we straw-hatted mortals packed onto Jackson Boulevard like pigs and cattle jammed into the Union Stock Yards to the south. Horns blaring from a few trapped motorcars and just let a horse try to enter. Reporters from all the papers, and photographers with their big cameras popping as they forced in to record the scene.

We wouldn’t know the facts of what was unfolding before us until we saw the morning editions, the sober stories chronicling the perished, how many’d died, and who. The very afternoon, the tallest, the closest, one of the ruffians bullied to the front may have seen it all, but the only dead body I glimpsed was slung over the shoulder of a fireman stepping down a ladder propped up against the bricks. One of the flyers, just a heap by then, could a been a suit of clothes coming down, rung by rung, on the shoulder of that courageous fellow.

A rumor whistled through about how the wrecked airship’d landed right on the vault and those at the front were grabbing wads of bills flew out with the window glass. That started more pushing and shoving and I nearly lost my hat, my sister Margaret’s hat, truth be told, had the wider brim I’d wanted for later, when my chum Gladys and me’d planned a stroll in the park. Gladys worked for the Cosmo Buttermilk Soap Company in our same building, the grand building she told me about after sickness forced me to quit the catalogue company where we’d met. Gladys usually did all the talking, me being the quiet type, and no doubt’d wanted to spool out another chapter in the romance she imagined with Charles Francis Brown—the artist had a studio on the seventeenth floor of our Marquette.

On account of the commotion that afternoon, we never did get our stroll. Gladys’d run up to seventeen seeking comfort from Charles Francis, though she claimed she wanted only a view out his window, faced south and west, from where she could see the terrible goin’s-on, never imagining that one of the heads under the hats belonged to me, Maeve Curragh. I had to pry off the lid to protect it, but when I found space enough to lift my arms and dig the hatpins out I could see the rim’d already bent in a way not intended. In the circumstances, Margaret would understand, and while she could not fix everything needed fixing, turned out, a hat’d never stumped her.

§

The papers? They did it somehow, managed to get a story in the last edition.

LEAPS FROM BALLOON ABLAZE!

Headlines standing like inch-high sayers of doom. Newsies shouting it and dressing up the story, praising the heroic firemen and they were heroes.

RICH AND POOR ALIKE PERISH!

yelled those dirty-eared boys had the imaginations, for they couldn’t a known yet who’d died. People flocking round at the car stop to grab a sheet still wet with printer’s ink, scraps from the morning editions and candy wrappers tamped beneath every kind of shoe. Reports blaring from front pages made a paper wall along the lineup.

WILSON IS ILL

KNIT WORKERS STRIKE FOR HIGHER PAY

HOUSE GIVES THE NOD TO HOME LIQUOR STORES

And there in the upper left box, under The Very Latest News, a paragraph telling how the dirigible’d been flying from Comiskey Park to the Loop all day, and hadn’t we seen it pass ourselves, from our office on the ninth floor of the Marquette? Heard the motors humming, glimpsed the shadow it made on the tall buildings, and flocked to the windows for the sight. Not much of a story so soon, but enough to report how the airship’d fallen burning and people after drifting through the sky in parachutes. “A gigantic flame shot skyward.” This time I knew more than the papers because I’d seen it all, yet didn’t it seem more real when you saw it printed? Right there in black and white, and not just me reading it, no. All the big shots mattered to the city’d read the same. Really everyone.

When I squeezed onto the Madison car the conductor watched my nickel drop into the box and asked me what I’d been up to with my hat tilted so, an ostrich feather straying from the crown and my hair nearly undone. But he didn’t say it neat like, talking directly to me and waiting an answer. Not that one with the peak pointed down his forehead like his wavy hair’s a line of geese he’s leading somewhere, the cap pushed up from his face flushed pink on account of the heat flowing in through the windows and from the temperature of passengers filled the facing forward seats, the benches, the standing room. No, not that one. He was regular on the Madison line, this one, a winker and a talker name of Desmond Malloy. I’d been pushed near up to a man saw him one evening and said in voice so loud you couldn’t help but hear, “Is it you then, Desmond Malloy? The conductor himself? And how’s your old da, lad?” He wasn’t a lad no more, the conductor, and said as much to the fella. They continued their blather over my head, about the da and his bum leg had to be taken off, and wasn’t it a sorrow for the mother and wasn’t he lucky then to have four strapping sons to help their folks, and had he heard the latest from City Hall?

The man got off same stop I did and I stepped down after him, but if Mr. Desmond Malloy took any notice of me, he showed no sign of it until the evening of the day of the Wingfoot Express. I’d watched him, though. A handsome fella, and kind, too, to help his da, but what got me first was the droll nature of the man. He had a patter same as Uncle Josh in the vaudeville and he laughed at his own jokes same as Uncle Josh, too, using us, the riders as his subject, teasing, and it lightened the journey sometimes felt long at the end of the day and rough when the car jolted to a stop on account of a horse and buggy blocking the rails, or someone running across.

“Don’t be shy, you with your feathers all ruffled. And her eyes sparkin’ like she’s got a new fella,” he said to the other pass

engers, most who didn’t hear, others who maybe smiled, because wasn’t he going on again, this conductor came to seem our own, often here at the end of the day on the Madison line. Not till he peered down did it became clear he was talking to me.

“Would that be the truth of it, miss?”

In the crammed-to-the-windows car, my face—not the roses and cream some girls had, but fair enough still to blush—broke out in little patches of perspiration commenced to funnel right down to the corners of my mouth, and my instinct was to flick my tongue out to catch the drops since I hadn’t the elbow room to dig for the handkerchief in my pocketbook. Sniffing, I said only if he’d seen what I saw, all the destruction and who knows how many killed, his eyes would be sparking too.

“What’s that, miss?” he asked, leaning close, face tipped over mine. “The crash and all the destruction? You were there, then? You saw it all? The dirigible of death?”

“Hadn’t I just been inside the bank myself?”

It came out as a whisper caused him to lean even closer, his breath a bouquet of tobacco and chewing gum.

“You’ve had the fright of your life now, haven’t you darlin’?” he said. “And you are darlin’, but you must have a name.” Before I had the chance to tell him I did indeed have a name and it was no business of his, he pulled himself straight up, raised his voice, called out, “Halsted Street. Next stop, Halsted!”

Thousands of workers at the Yards’d walked out on Friday, but they’d walked back in today and those didn’t live near could change at this corner for the Halsted line would get them to the Yards. Bodies crushed toward the door, separating the conductor, Desmond Malloy, and me. I watched the shoulders of his dark blue uniform bobbing among, and mostly above, the rest and when I got to the door myself there he stood with a rolled-up Trib.

“Have you seen the mornin’ news, dear?”

Dear, was it now? And him aiming the paper towards my crooked elbow, poking it into the V it made along my sweaty side, me dipping my head in thanks and, with one hand on my hat, stepping onto the cobblestones slashed by the steel rails. And then, topping it all, didn’t he wave at me? I laughed, despite the sad story I had to tell them all at Bridey’s that night on West Monroe, up the block where most everyone had yet to learn about the terrible goin’s-on downtown.

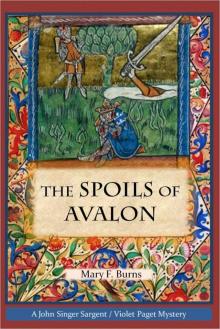

The Spoils of Avalon

The Spoils of Avalon The Reason for Time

The Reason for Time J: The Woman Who Wrote the Bible

J: The Woman Who Wrote the Bible